15 Accidental Medical Discoveries – Part II

The road to discoveries in medicine is anything BUT the scenic route. It is convoluted and littered with failure; however, it does contain more than its fair share of brilliant serendipity which continually alter the course of human suffering and change its practice forever.

At least one group of people weren’t always happy about Penicillin

Our adventure “behind the curtain” of medical research began in part one with the first six of 15 or so accidental medical discoveries—from microscopes to Viagra.

Now, here are some more who owe their origin to “happy accidents,” coupled with a receptive, curious and prepared mind of someone who pursued answers to questions.

Accidental Medical Discoveries

Anything BUT the Scenic Route

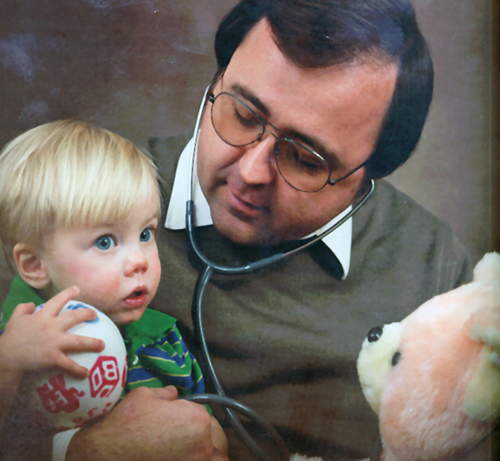

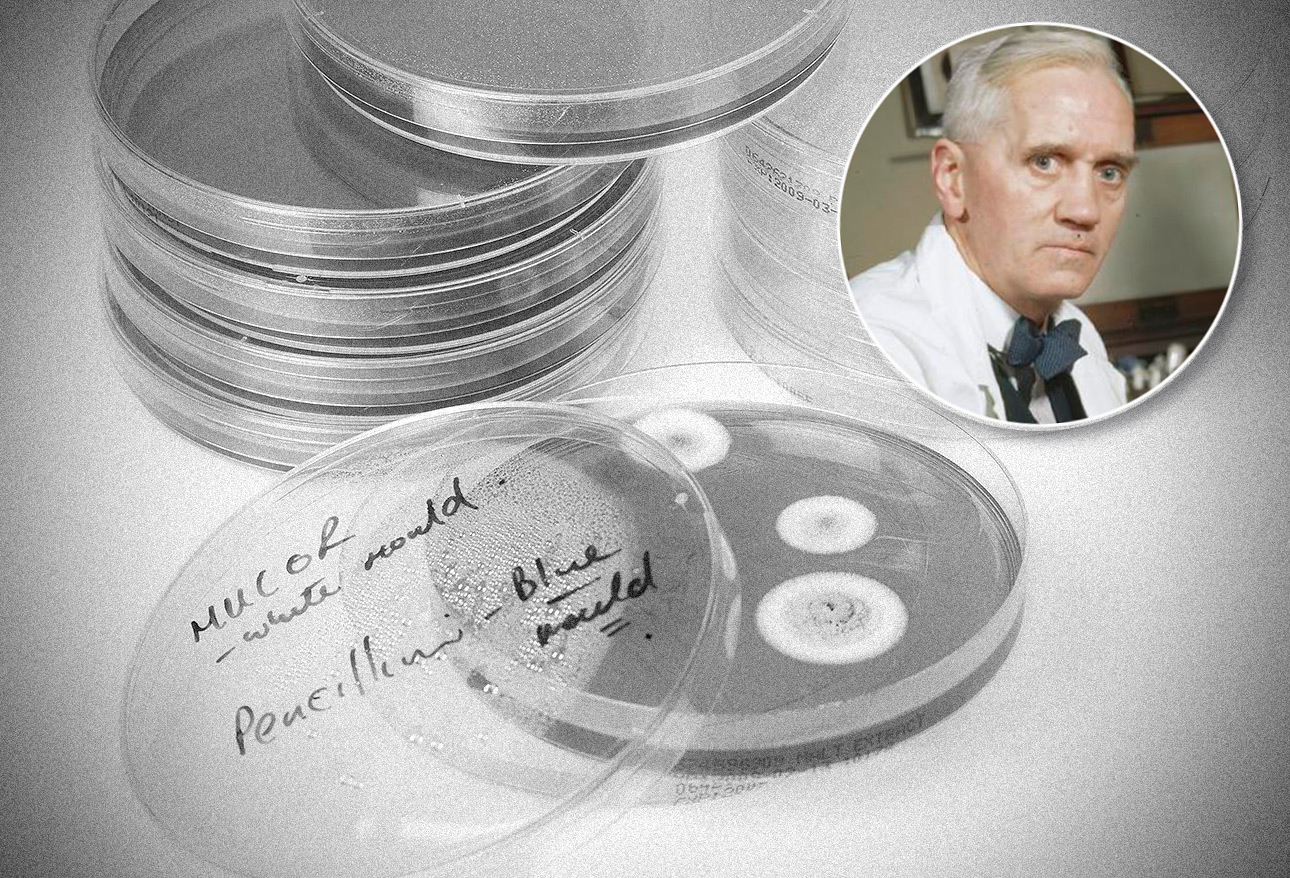

Alexander Fleming (1881-1955)

Discovery and Contribution: Discovered Penicillin (1928); ushered in the age of antibiotics.

You can call this a complete “accident” if you want but how many of you would look at a spoiled glass jar full of mold (or as they say in Scotland: mould) and not just chuck it in the garbage can (or as they say in Scotland: the bin)?

How many of you would look at it and wonder about the colors, how many kinds of things were growing, was that mold or bacteria… and even more specifically: “why are those things NOT growing over there?”

That’s what Alexander Fleming, a Scottish bacteriologist did when, coming back from a 2-week holiday in 1928 and finding he’d left a petri dish full of Staphylococcus aureus culture out on the counter and it had also started growing colonies of mould (it was Scottish mould after all).

Truly, I can’t believe for a second that his first thoughts went right to the fact that the Staph was growing all on the other side of the dish from the mould. Surely, something must have captivated his curiosity and caused second and third looks until the phenomenon dawned on his consciousness.

To his (and our) everlasting credit he then did a whole lot more than just say “hmm, that’s odd” and head for the bin. He found that it was only a certain kind of mould and then just a certain species of that mould that inhibited Staph: Penicillium notatum to be exact. And it wasn’t just Staph that it inhibited, some other things too.

Fleming was a consummate researcher and bacteriologist. He discovered a lot of things about Penicillium: some species killed, others just inhibited and others did nothing; but, he wasn’t a production guy.

Isolating and producing the active antibiotic was left to other smart people; and, because of the war breaking out, came to the US where full-scale production could be identified using a different species of mold (this was true US bred) found in the garbage can of a Peoria Illinois restaurant on a moldy cantaloupe… and lives saved.

Before the dust had settled Fleming, Ernst Chain and Howard Florey got a Nobel Prize, Jasper Kane and Pfizer had found the cantaloupe, chemical engineer Margaret Hutchinson Rousseau invented deep-tank “corn steep” production and 2.3 million doses were produced in time for the invasion of Normandy in the spring of 1944.

THAT, my friends, is why MY MIND just can’t get traction around calling this merely AN ACCIDENT! Fortuitous, serendipitous, a miracle… but this took a lot of well trained, very smart and thoughtful people with the integrity to do their jobs correctly and fully!

Amazingly, even the government’s war Production Board came through and by June 1945 over 646 billion units per year were being produced which saved an estimated 12-15% of lives and G. Raymond Rettew had seen to it that commercial quantities of penicillin were being produced for those at home.

Karl Paul Link (1901-1978) and Mark Arnold Stahmann (1914-2000)

Discovery and Contribution: Warfarin (1940); oral anticoagulants to prevent clotting

I kind of wince at the thought of a cow bleeding to death; but, in 1933 that’s what was happening to cows on a particular Wisconsin farm. Needless to say it didn’t do the farmer any good either but he had no luck solving the problem with anything he did or anyone he asked for help.

The “accidental” part started with the completely serendipitous meeting of the farmer and a wet-behind-the-ears agricultural chemist, Karl Paul Link, at the Experiment Station of the University of Wisconsin in Madison.

Raised in the 30’s, Link wasn’t schooled in the “Duh, I guess that’s just how they make cows” kind of response they teach our kids today and he actually made the effort to try and solve the conundrum with the aid of his lab manager Mark Arnold Stahmann.

Link uncovered that it was coumarin which was being generated in the cows’ spoiled sweet clover feed that was causing them to hemorrhage; then, after 7 years of hard science, that the spoiling process converted the coumarin into dicumarol which interfered with the clotting properties of vitamin K inside the body. That, of course, wasn’t the accident.

Eventually, Stahmann produced several varieties of the compound and named it WARF-arin (Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation – get it?), patented it and sold it for rat poison.

It was highly potent (deemed too much so for human consumption) and had a delayed action; so was a very successful product against rats who would take some back to their den, share it, get sick somewhere else besides the house and die.

No good deed goes unpunished I suppose. A young Navy recruit eventually used it to attempt suicide by drinking some and in the process of saving his life his physicians had shown that it was indeed “safe” for human consumption and filling a need to prevent clotting events in people with many other types of illnesses.

It is marketed as Coumadin and, until quite recently, was the only thing approximately 2 million Americans could take to prevent clotting events. And, even though heparin and streptokinase were already known, it was Coumadin which launched the era of oral anticoagulants.

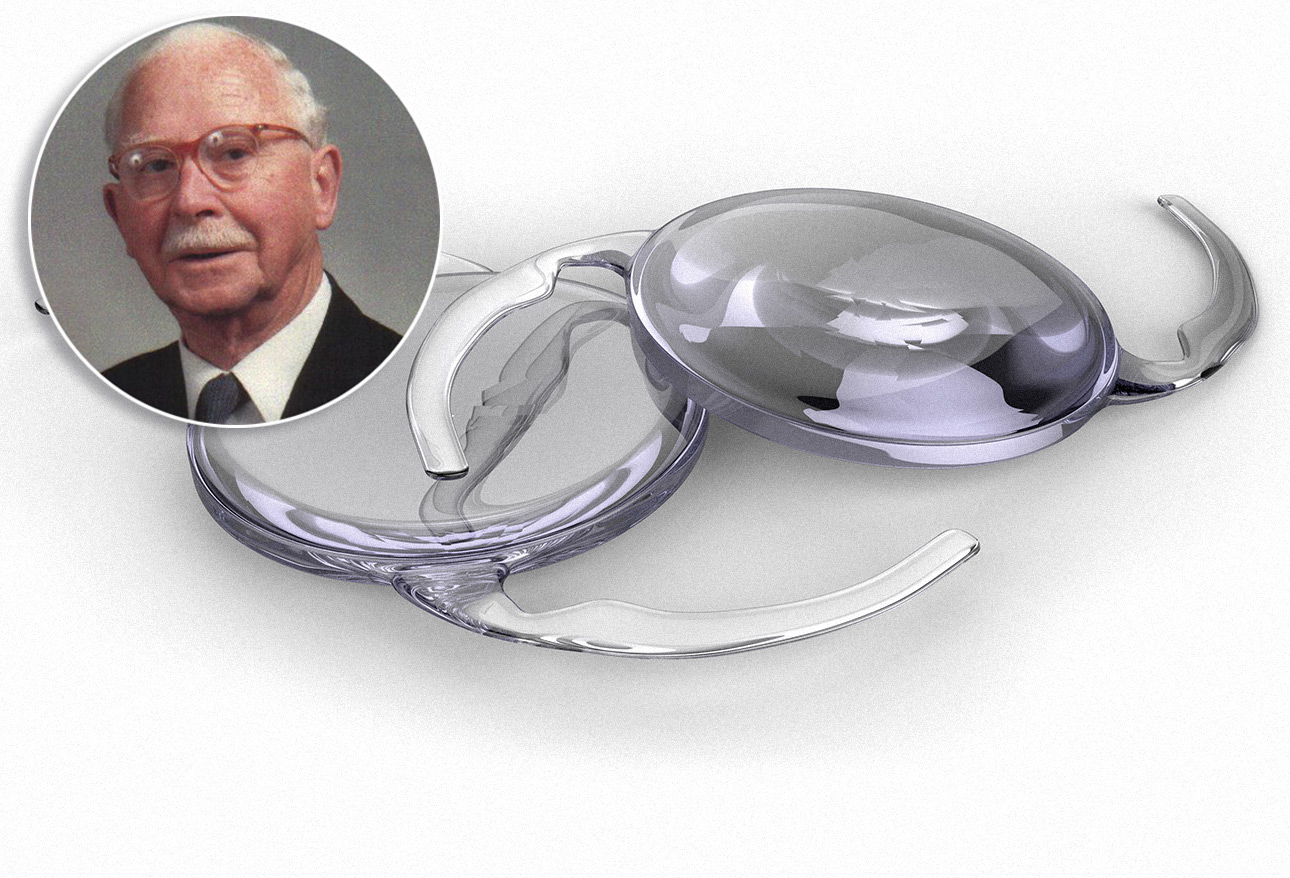

Harold Ridley (1906-2001)

Discovery and Contribution: Intraocular Lens (1949); prevent one of the chief causes of blindness

Doctor Nicholas Harold Lloyd Ridley was an ophthalmology surgeon during World War II and happened to treat a Royal Air Force pilot, Gordon Cleaver, whose eyes had been damaged by some plastic shards.

Over the course of treatment Ridley paid attention to the fact that, even with all the trauma, his eyes had not actually reacted adversely to the presence of the plastic and began wondering if that fact could be used somehow to help others suffering from different diseases—cataracts, for example.

Years of subsequent research later, that observation led to a cataract surgery in 1949 when Ridley replaced a consenting patient’s cataract with an implanted plastic lens—obviously considered a HIGHLY-controversial and daring operation… and yes, obviously with success.

Despite the “haters” who seemed to come out of the woodwork in anger, his AND HIS PATIENT’S fearless decision paved the way for vastly improved outcomes in cataract surgery and in the lives of countless millions.

Leo Sternbach (1908-2005)

Discovery and Contribution: Benzodiazepines (1959); antianxiety and relaxing drugs

On the eve of World War II, Leo Sternbach was innocently in his University of Krakow (Germany) chemistry lab investigating some tricyclic compounds that could be used in the textile industry as dyes.

A few years later (the 50s) he was in his lab at Hoffman-LaRoche (New Jersey) and decided to take another run at a few of the tricyclic compounds he had previously isolated. And the rest, as they say, is: History; because, that led to the discovery of benzodiazepines, a class of drugs which includes diazepam (Valium) and chlordiazepoxide (Librium).

Over ten or so of the compounds they had isolated for testing all turned out to be biologically inactive. Literally however, in the kind of thing movies are made of, one lorn, forgotten sample which had kicked around the lab and never got complete testing finally was saved from complete destruction and oblivion. Then, at the last minute, it made a mouse so contented that you could almost see the grin on its face.

The test was replicated and the compound turned out to have extraordinary tranquilizing properties. Librium was born and soon followed by Valium which began a whole new billion-dollar industry of about 30 different benzodiazepines used for anxiety, muscle relaxation, sleep disorders, anesthesia and epilepsy.

Sternbach was named one of the most influential Americans in the 20th century by US News & World Report.

Charles Dotter (1920-1985)

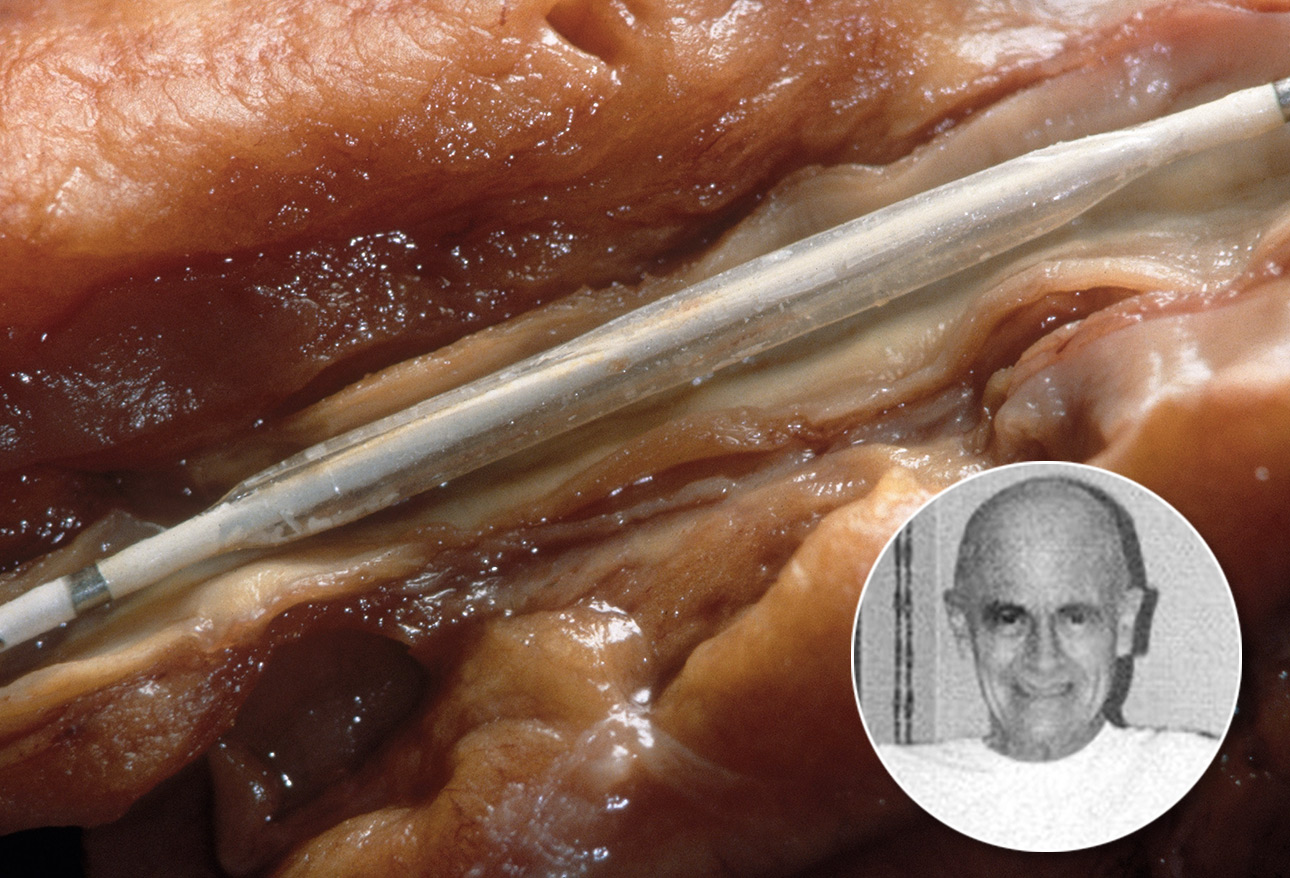

Discovery and Contribution: Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty (1963); interventional radiology

Charles Dotter was a radiologist who became the “father” (the hard way) of interventional radiology and a giant of 20th-century medicine.

In his time a lot of work was being done trying to figure out how to diagnose, deal with and treat all kinds of circulatory diseases especially those caused by obstruction to an artery.

Someone else had already invented arterial catheters and he was trying not only to gain skill but to see how making diagnoses could be easier and better in the “cath lab.”

He developed a technique, quite by accident, where the catheter is jammed through an arterial obstruction to dislodge the blockage. Having done it once to find that it actually worked, he pioneered the procedure which came to be known as the “dottering technique.”

He went on to create several other interventional techniques in addition to percutaneous transluminal angioplasty such as flow-directed balloon catheterization, the double-lumen balloon catheter, the safety guide-wire, the concepts of percutaneous arterial stenting, and stent grafting—to name only a few.

Creating interventional radiology paved the way for coronary angioplasty and the growth of the interventional cardiovascular techniques we rely on today.

Barry Marshall (b. 1951) and Robin Warren (b. 1937)

Discovery and Contribution: Helicobacter pylori and Ulcers (1982); Revolutionized Dx/Rx of world’s most prevalent bacterial infection

I don’t remember practicing medicine without Penicillin BUT I do remember trying to treat ulcers before two “wise guys” down in Australia came up with the idea that they were caused by bacteria!

I’m one where facts usually and fairly easily convince me; but, I mean, this is the stomach we’re talking about. Full of acid. How could any bacteria even grow in such a place? Let alone long enough to cause infection. It didn’t make “intuitive sense” and must be just a contaminant of their samples, right?

Nope. Patients actually improved with antibiotics AND accidentally leaving an agar plate incubating longer than intended actually gave us the name of the bacteria: Helicobacter pylori.

Barry Marshall and Robin Warren had found the bacteria that caused the disease and were able to grow it in their petri dishes and incubators; but, didn’t know specifically what it was—probably a Campylobacter. Leaving the dishes incubating over a long holiday weekend showed that it was an entirely new genus.

The facts that Marshall and Warren had to fight against so much nay-saying and ridicule, that their “absurd” claims flew in the face of accepted medical knowledge and that such an enormous percent of the world’s population suffer from ulcers netted them the Nobel Prize in Physiology/Medicine in 2005.

4 Posts in Accidental Discoveries (accidental) Series

- Part 3: X-Rays, PAPs, Pacemakers, Rogaine, Antabuse, Pancreas-Diabetes – 15 Mar 2018

- Part 2: Penicillin, Warfarin, Eye Lens, Benzodiazepines, Interventional Radiology, Ulcers – 13 Mar 2018

- Part 1: Microscopes, Vaccination, Anesthesia, Bacteria Cultures, Viagra – 3 Mar 2018

- Accidental Discoveries: Intro/Index – 2 Mar 2018