Parenting: Attitudes – Unintentional Learning

With all deference to teachers, I am becoming more impressed that children do most of their learning when not actively being “taught”. At least in things that “count.”

The aspects of life, which are critically important to a child’s personality, are his attitudes, about: self, others, systems, things, and life in general.

Most parents know intuitively what types of things instill wrong attitudes in children and we may have even caught ourselves or neighbors saying such things as:

“You make me sick,” “You’re the dumbest thing I’ve ever laid eyes on,” “That teacher can’t make you do that,” “You’ll never amount to anything, you’re too lazy,” or “you’re just like your father (or mother).”

Or “Don’t play with him, he’s retarded,” “Can’t you get a better-looking date than that?” “We don’t play with them, they’re not our religion.”

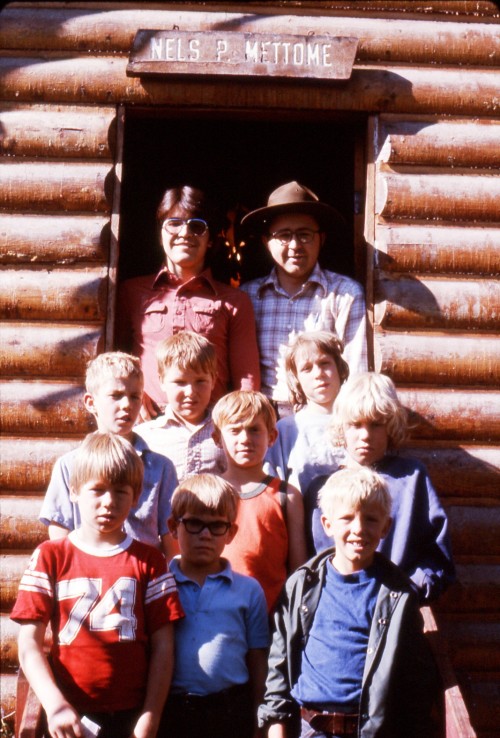

In younger days during medical school, I was involved in the children’s diabetic camp group. Counselors spent one to two weeks in the mountains with the children teaching them self-sufficiency.

We were also encouraged to follow-up friendships throughout the year through our own little “mini camps.”

The aspects of life, which are critically important to a child’s personality, are his attitudes, about: self, others, systems, things, and life in general.

The truly amazing thing was that our camper “friends” were not the same children we saw repeatedly admitted to the hospital for complications of diabetes!

There were two boys in a cabin I was responsible for, that couldn’t have been more different. One was slightly older, happy, cooperative and very well-liked by both campers and counselors. He willingly participated, tried new things, accepted criticism well and seemed to let life happen and give him experience.

The other, a slightly smaller boy, struggled the whole time. He seemed unhappy with nearly everything and “bad” things seemed to be always happening to him. He hated change, wouldn’t try new things, had to be talked into most activities and couldn’t at all accept criticism.

Insulin Injections just a Part of Life

What a difference in the boys! And it was even more apparent because they were in the same cabin and always together. In a odd sort of way they became friends.

Most counselors were as perplexed as I over the difference. What could make it so? Was the one boy’s difficult attitude because he was always having “problems” with his diabetes or life – or did he have problems because he had a difficult attitude?

The enigma was made a bit clearer on the last day when their parents came to pick them up. They both came over to speak with me. I saw that the older boy’s father was walking with a slight stiffness, which I eventually found to be due to an artificial leg.

You see, there had been no “self-pity” attitude in their household over the boy’s diabetes. Dad had difficulty as well – and who could say which was “worse.” Later I even asked the boy why he seemed to tolerate his diabetes so well and his reply was “dad has it harder than I do.”

Was the boy’s difficult attitude because he was always having “problems” with his diabetes or life – or, did he have problems because he had a difficult attitude?

Most of us at the camp rapidly discovered that our camper’s physical condition dramatically reflected their attitude.

And do you know, you can teach a child a changed behavior without him even knowing it!

While living in California, one of the children who went to Disneyland with us was an eleven-year-old, hyperactive patient of mine.

Having two rolls of nickels, I explained the rules of a game he and I were going to play during the day.

I told him that every time he did a certain something that I had in mind, I would give him get a nickel. His task was to try to figure out what it was that he would do that would earn him a nickel; and, at the end of the day we would count how many he had “earned” and he needed to tell me what it was that he had been doing to earn the nickel.

What I did all day long was to reward every act of courtesy that I saw him perform, … to anyone. He would be courteous and a few moments later I would hand him a nickel to put in his pocket.

All morning long he had only earned three nickels, and I thought that the experiment was not working; but, after lunch, (and my making a great deal of effort to show extra courtesy to him) his “nickel earning” (and acts of courtesy) picked up. By the end of the day he had become so inordinately (for him) courteous, that I thought for sure he had figured it out and was determined to clean me out of nickels. In the last hour I kept track, and he earned eight – about one every 7 minutes!

In all, he had earned a whole roll and a half of nickels; but, you know, he had no idea why, and could not verbalize the rule – even though all day he had opened doors, voluntarily returned lost tickets, gave up his parade seat to a woman with a child, and went out of his way to say “excuse me” or “pardon me.” His courtesy had dramatically increased throughout the day through example and rewards for doing something right even though he didn’t know why.

All of this unconsciously – and I should note that it also had a profound effect on all the others that were with us in the park that day even though they never learned of our “game.” Then, at his next routine checkup three weeks later, his mother (who I had told what we had done) said that it was still with him!

Later, I mentioned this “game” to someone else, who I was counseling about parenting, and he tried it on his ten-year-old using kisses. Within several hours he switched to hugs and then pats on the head – and what he was most surprised at was that: he had never even told his son of the game! His son had been completely responding to subconsciously correlated positive rewards.

Our boys might not need a special lesson on how to treat girls, when they have a father who pulls the chair out at the dinner table for their mother, holds the door open for her and their sisters, and in other ways shows deference.

Boys who are taught to do the same thing for their mother and sisters, usually don’t have to be taught that “You never, ever hit a girl.”

Family lessons on courtesy to others are much more effective when the children’s mother and father make the phrases, “thank you,” “I’m sorry,” and “excuse me,” a liberal part of their daily vocabulary, even to their children.

Be careful, because children learn both what you intend and don’t intend to “teach.”

One time, on an outing, a little diabetic patient of mine had just about taxed my patience to the limit with his “center of attention” antics.

Mostly for my own benefit in remaining calm and positive, just as he was going to poke another child and didn’t know I was watching, I preemptively startled him by picking him up, swinging him around in a hug, and telling him, “I can’t believe how much I like you.”

I wasn’t intentionally giving him a lesson, merely trying to keep myself centered on the real purpose of our outing; but the incident must have lurked about the recesses of his head for many months.

Much later, on another outing, after I had completely forgotten about it, he snuck up on me from behind during a game of keep-away and tackled me completely to the ground. He ended up on top of me and with a chuckling smirk that told everyone he was mightily pleased with himself, he repeated to me back the same words I had used on him several months before.

Be careful, because children learn both what you intend and don’t intend to “teach.”