Ear Infections: Misdiagnosed, Overdiagnosed – New Guidelines Released

Clearly, and by a huge margin, ear infections are the most common diagnosis in all of pediatric medicine. Did I say by a large margin? Clinician visits for Acute Otitis Media (“middle” ear infection – AOM) in 1995-96 were 950 per 1000 children seen! [Makes one wonder who were the 50 that didn’t have an infection]

And the accurate diagnosis is difficult even for the most experienced pediatrician; not to mention for parents, physician extenders, family medicine or any physician whose practice isn’t devoted exclusively to children.

Diagnosis of ear infection

First, you’re looking down a tiny tube using only one eye at, usually, a moving target. The ear drum is usually smooth and translucent and moves freely. BUT ear canals get full of cerumen blocking the view, kids cry making the drum artificially red, it’s stand-on-your-head difficult to see motion of the drum AND did I say kids cry?

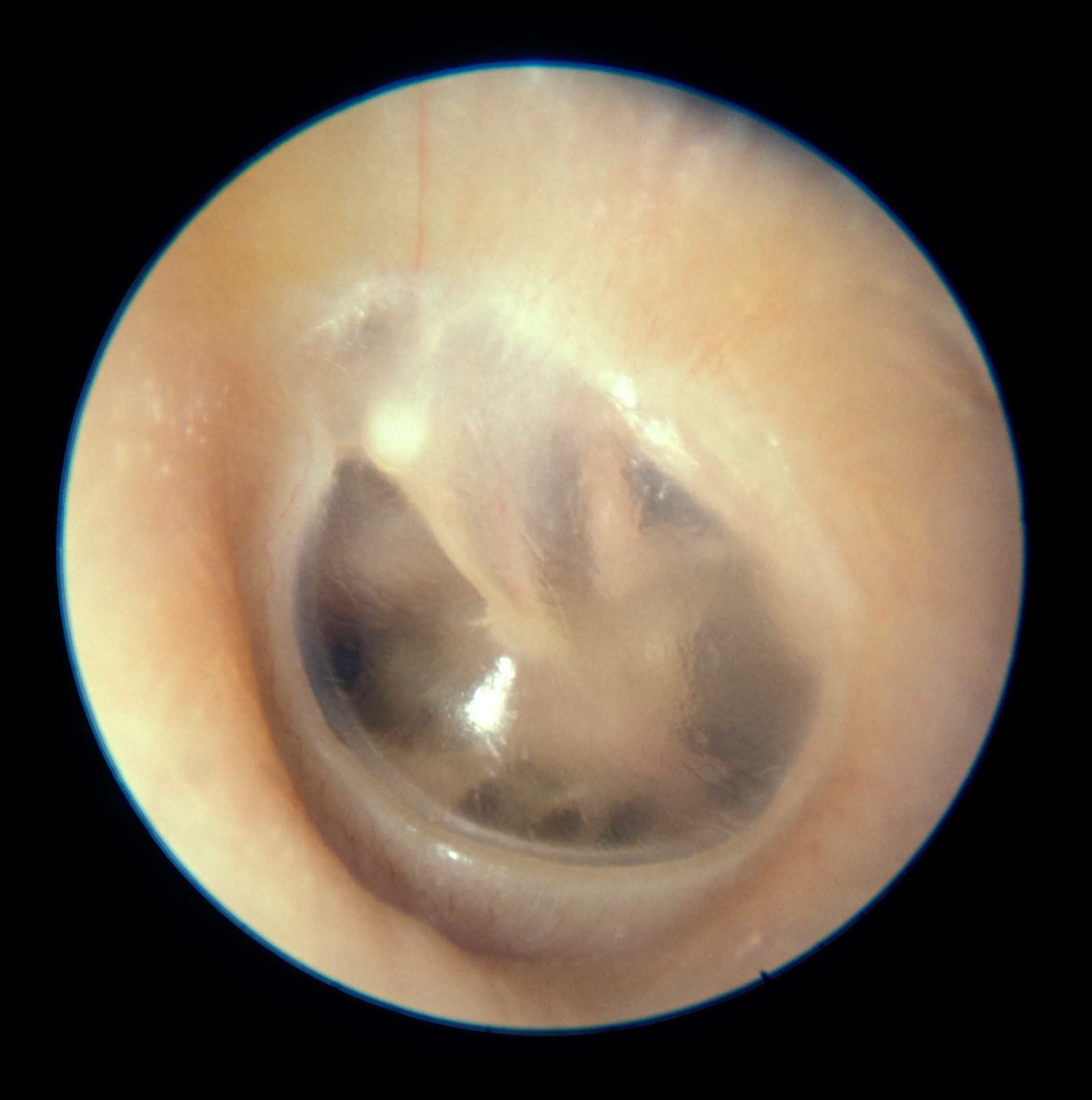

I’ve been using an “insufflator” attached to my otoscope ever since medical school – a long time ago. It’s a little gadget that can give a tiny puff of air pressure when you’re looking at an ear drum designed to make it move. If it will only move out but not in – the drum’s retracted. If it hardly moves at all – there’s fluid or pus behind it. If it moves great – even though it’s red – then it’s probably not infected and only red because of crying.

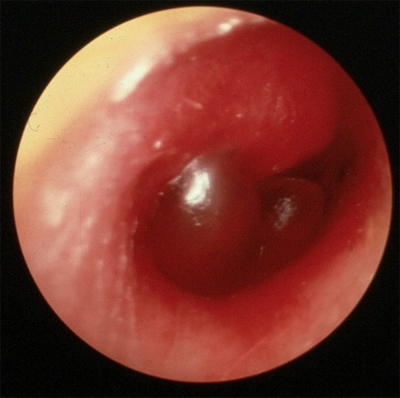

There can be an infection of the canal causing pus and that’s called “otitis externa” – swimmers ear. Often, in this infection, there is pus draining from the ear. On the other hand, if a middle ear infection causes the ear drum to break open, pus may drain from the ear too before it heals itself – most of the time.

And just to make matters even more complicated some people call ordinary fluid behind the ear drum an ear infection too. Except there is really no infection, just left over fluid from a previous infection or allergies etc. That’s called “serous” (meaning fluid) otitis media or “otitis media with effusion (OME) – an entirely different colored horse.

A real life example of the difficulties was brought home to me fresh out of Utah medical school when I entered residency in California. It was as if I’d never seen this disease before and my colleagues looked at me funny when I talked about it. You see, in California children with otitis media got better. In Utah they hardly ever did! At least on the first course of antibiotics.

Diagnosing ear infections

Unfortunately, the fact that it’s difficult to diagnose – AND besides who’s going to check up on you – makes it a favored “wing it” diagnosis for someone who can’t really see the drum, who isn’t going to take the time to clean wax or restrain a child, who isn’t using an insufflator OR who is just simply rushed. The thinking is: “the kid looks sick (or I just want to cover all the bases), I want to use antibiotics, I’ll call it AOM cause it probably is anyway.” Really, it happens more often than you think.

From a parents standpoint, once you know the steps that a doctor needs to take to make an accurate diagnosis, and you see what he does as the child is acting the way he is, you can probably surmise how accurate the current diagnosis is. Sometimes the doctor will even admit that “this was a tough exam and I couldn’t see the drum well.”

Why does it matter?

So what’s the big deal and why does it matter? Can’t we just treat them all with antibiotics and be done with it? HECK NO! That’s what has been going on for several years and now we’re getting stuck with all kinds of RESISTANT strains of bugs that we can’t kill!

In fact, even though the problem has been known about for years, until recently doctors have been without motivation to change habits and besides every grandmother that comes in to the office just KNOWS that ear infections NEED to be treated with antibiotics “and by jingo we want them.”

It may take a couple of notable cases where people die of infections we can’t treat – like the Muppet’s Jim Henson – but people do get the message eventually.

And this doesn’t even take into consideration the need to have an accurate diagnosis in order to prevent unnecessary surgery! Children with “too many” ear infections often end up with surgery to place PE tubes so the middle ears can drain.

New treatment recommendations

There has been an effort by physicians to correct the overuse of antibiotics over the past seven or so years. In fact, by 2006 the number of clinical diagnoses of acute otitis media was down from 950 to only 634 per thousand children seen. Of course, there was a simultaneous decrease in the amount of antibiotics prescribed too. From 760 to 484 per thousand.

Updated American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) clinical practice guidelines address the diagnosis and management of uncomplicated acute otitis media (AOM) in children aged 6 months to 12 years. The new recommendations, which offer more rigorous diagnostic criteria to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use, were published online February 25 and in the March issue of Pediatrics.

However, it “aint over yet” because OM remains the most common condition for which antibacterial agents are prescribed for children in the United States. An exhaustive review of all the new things we’ve learned the past few years has been completed by the AAP (American Academy of Pediatrics), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the So. California Evidence-Based Practice Center. And, we now have updated clinical practice guidelines.

Chief findings are that we need to take into account patient age and symptom severity but AOM may be managed with antibiotics and analgesics OR with observation alone. The whole point is to obtain more accurate diagnoses and to reduce even further the unnecessary use of antibiotics.

Here are the specific action statements from the guidelines:

- AOM SHOULD be diagnosed when there is moderate to severe tympanic membrane (TM) bulging or new-onset otorrhea (draining) not caused by acute otitis externa.

- AOM MAY be diagnosed for mild TM bulging and ear pain for less than 48 hours or for intense TM erythema (redness). In a nonverbal child, ear holding, tugging, or rubbing suggests ear pain.

- AOM should NOT be diagnosed when pneumatic otoscopy and/or tympanometry do not show middle ear effusion. [Some physicians don’t currently do either]

- AOM management should include pain evaluation and treatment.

- Antibiotics should be prescribed for bilateral or unilateral AOM in children aged at least 6 months with severe signs or symptoms (moderate or severe otalgia [ear pain] or otalgia for 48 hours or longer or temperature 39°C or higher) and for nonsevere, bilateral AOM in children aged 6 to 23 months.

- On the basis of joint decision-making with the parents, unilateral, nonsevere AOM in children aged 6 to 23 months or nonsevere AOM in older children may be managed either with antibiotics or with close follow-up and withholding antibiotics unless the child worsens or does not improve within 48 to 72 hours of symptom onset.

- Amoxicillin is the antibiotic of choice unless the child received it within 30 days, has concurrent purulent conjunctivitis, or is allergic to penicillin. In these cases, clinicians should prescribe an antibiotic with additional β-lactamase coverage.

- Clinicians should reevaluate a child whose symptoms have worsened or not responded to the initial antibiotic treatment within 48 to 72 hours and change treatment if indicated.

- In children with recurrent AOM, tympanostomy tubes, but not prophylactic antibiotics [we used to do this all the time], may be indicated to reduce the frequency of AOM episodes.

- Clinicians should recommend pneumococcal conjugate vaccine and annual influenza vaccine to all children according to updated schedules.

- Clinicians should encourage exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months or longer [shown to decrease illness including ear infection].

Conclusion

So, what do you think? Those of you who have experience raising kids will recognize some differences. The take home to what these recommendations mean now, is that:

- Ear infections are known to get better on their own without antibiotics, we’re gonna let them do it more often.

- Especially older children may go home with prescriptions to get filled ONLY if they don’t improve in a few days.

- You should start seeing your doctor do insufflation when he examines the ears and/or more typmanograms to look for middle ear fluid.

- We’re not going to jump on prophylactic antibiotics like we used to. Instead it’s referral to the ear doctor for possible tubes.

- We’ve got to be more insistent on making an accurate diagnosis to avoid unnecessary surgery and antibiotics.

- You’re going to need to be more vigilant in: not letting anyone smoke around the kids, avoiding things they are allergic to, keeping to the scheduled immunizations and notifying the doctor if any antibiotics don’t seem to be working.

[Pediatrics. 2013;131:e964-e999.]

Advertisement by Google

(sorry, only few pages have ads)