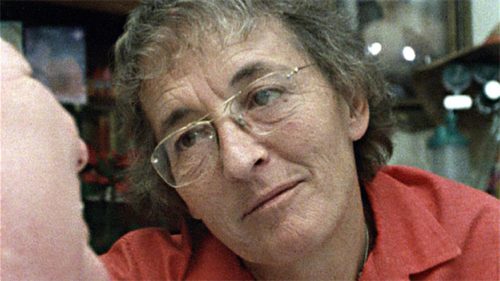

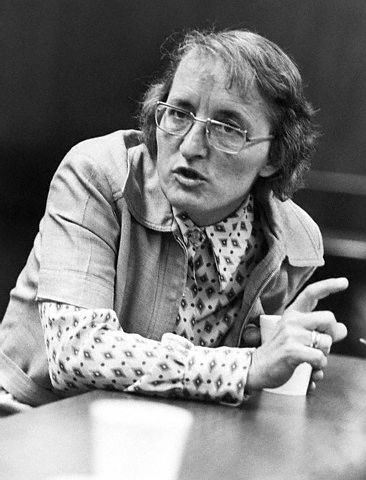

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

Despite dealing with it—and often even causing it—the medical profession woefully neglected the slightest consideration of “dying” until 1969 when Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross wrote “On Death and Dying” about her experiences with terminal patients.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross: On Death and Dying

Incredibly, being disqualified from her chosen pediatric residency because she was pregnant caused her to choose psychiatry and become one of the 50 most influential physicians of all time!

Her capacity for compassion literally transformed the practice of medicine in a way no other has. An ordinary woman doing extraordinary things with her life.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross (1926-2004) – #33

Taboo Breaker, Medical Care Transformer, Hospice Founder

Number thirty-three on the list of all-time influential physicians, Dr. Kübler-Ross, like so many other women in medicine, became a doctor in “spite of” not “because of” the many around her giving advice, placing barricades and withholding help.

Early Life and Education of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

Elisabeth Kübler was born weighing only two pounds, the first of triplets (Erika and Eva), on July 8, 1926 in Zürich, Switzerland, to Ernst Kübler and Emma Villiger-Kübler.

She gave little about her early life to public biographers except that it was in line with the Swedish-Protestant-Christian ethic of: “work, work, work.” She said she was taught that “you are only a valuable human being if you work” and retrospectively analyzed “I myself have danced and played too little.”

She received intense resistance of her aspirations to medicine by her father who told her that she, at age 16, could either work as a secretary in his business or go become a maid. Her decision was to do neither and left home.

She worked at a series of jobs and eventually volunteered to help in hospitals and care for refugees in World War II. She helped in many war-torn communities after the war, including the polish concentration camp Maidanek where she was profoundly affected by the hundreds of butterflies carved into some of the walls by prisoners struggling to cope facing death.

She returned in 1951 to pursue her dreams of becoming a doctor, as a medical student at the University of Zurich. Meeting an American medical student, Emanuel Robert Ross, she waited for him for a year after she graduated in 1957; then marrying in 1958 they both moved to Long Island New York where they interned at the community hospital.

Her desire was to become a pediatrician but she was disqualified from the New England programs because she was pregnant. Instead she diverted to Manhattan State Hospital where she specialized in psychiatry.

She was appalled by the hospital treatment of patients in the U.S. who were dying and the fact that there was nothing in the curriculum at the time which addressed it. She began giving a series of lectures featuring terminally ill patients, forcing medical students to face people who were dying.

In 1962 she accepted a position to instruct at the University of Colorado School of Medicine in Denver and completed her training in psychiatry in 1963.

Filling in for a colleague one time, Kübler-Ross brought a 16-year-old girl who was dying from leukemia into the classroom. She told the students to ask the girl any questions they wanted. But after receiving numerous questions about her condition, the girl erupted in anger and, according to an article in the New York Times, started asking the questions that mattered to her as a person—such as what was it like to not be able to dream about growing up or going to the prom.

Career

In 1965 she became an instructor at the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Medicine and there developed a series of seminars using interviews with terminal patients—drawing, as one would expect, both praise and criticism.

She occasionally questioned traditional psychiatry practices she observed when undertaking 39 months of classical psychoanalysis training in Chicago.

Her compassionate and extensive work with terminal patients led to her experiences being turned into a book: On Death and Dying, in 1969—still considered today the single most seminal work in medicine on the subject.

In it she described for the first time the famous “five stages of grief” as a pattern of adjustment which is now parroted and used in many other fields: denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.

Life magazine ran an article on Kübler-Ross in November 1969, finally bringing awareness of her work to the public outside of the medical community. The response was enormous and influenced Kübler-Ross’s decision to focus on a career of working with the terminally ill and their families. The intense scrutiny her work received also had an impact on her career path. Kübler-Ross stopped teaching at the university to work privately on what she called the “greatest mystery in science—death.”

Later life:

It’s probably fair to say that “compassion” was her claim to fame and her life’s work. She sometimes seemed consumed by consideration for others who were facing death and the daunting task of teaching, instilling or shaming others of her profession into showing a little of the trait as well.

She lectured, she wrote prolifically, she set up and organized hospice, she championed the care of AIDs patients, she bought a farm and turned it into a hospice of sorts and, of course, faced the most vitriolic of opposition from bigoted people in all kinds of costumes. Dealing with those facing death meant that she dealt with those whose priorities basically precluded dishonesty, guile and subterfuge; which, unfortunately, made her an easy mark.

Eventually, she became interested in issues of life after death, spirit guides, and spirit channeling, which was met with skepticism and scorn by her peers in the medical and psychiatric circles. She was even terribly duped and conned by Jay Barham and his Church of the Facet of the Divinity who was eventually revealed to be nothing but a sex pervert.

She envisioned and attempted to establish a hospice for infants and children infected with HIV to give them a last home where they could live until their death but was blocked by bigoted Virginians who prevented the necessary re-zoning and then lost her home and possessions to an arson fire set by opponents of her AIDS work.

Besides the un-defendable opposition to her work, her life wasn’t without difficulties. She had two miscarriages before delivering two children: a son Kenneth and a daughter Barbara in the early ’60s.

A large series of strokes in 1995 left her partially paralyzed and her Shanti Nilaya Healing Center closed around that time. Shortly after that, in 1997, her husband requested a divorce.

Dying In A New World Of Medicine She Made:

This woman who had received 20 honorary degrees, taught over 125,000 students in death and dying courses all over the world, had delivered the 1970 Ingersoll Lectures at Harvard University and written over 20 books, just liked and dealt with people simply. She wanted to be called Elisabeth, the Kübler-Ross moniker was too formal and pretentious for her, she said, referring to herself as a Swiss Hillbilly.

Better than any, she understood the stages of grief but, believe it or not, was actually criticized by some when she became frustrated and angry at her illness. Later she was asked about it: “People love my stages, they just don’t want me to be in one.” “I am like a plane that has left the gate and not taken off,” she said, “I would rather go back to the gate or fly away.”

In the world as it was when she trained in medicine, death was not discussed or even seen. Patients who were dying were stigmatized and put in the furthest room from the nursing station. I remember that very thing happening at a hospital I worked in during my pre-medical college days.

Her life’s work and dream for the dying was simple and natural: surrounded by loved ones in a home-like setting instead of in a far-off hospital corridor.

Because of what she had done with her life, in 2002 Elisabeth was able to move into a hospice where, with a co-author, she finished her last book: On Grief and Grieving.

Because of her battles with bigotry, her death on August 24, 2004, of natural causes, included all the ordinary pleasures that she had so passionately advocated for over the years — her room with lots of flowers, a large picture window, loved ones, her grand-kids playing at the foot of her bed.

The very “ordinary” nature of her death exemplified that the radical change she created had by then become a reality.

Because of Elisabeth, the way all of us view death will never be the same.

Biographic Summary

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross was a Swedish-American psychiatrist who revolutionized the care of the terminally ill, helped found the hospice program and wrote the definitive book: On Death and Dying

Born: July 8, 1926, Zürich, Switzerland

Died: August 24, 2004 (78), Scottsdale, Arizona

Education: University of Zürich medical school in 1957;

Known for: Championing the ethical and compassionate treatment of the terminally ill, the hospice movement, AIDs treatment

Books: Over 20 including: On Death and Dying, To Live Until We Say Goodbye, Living with Death and Dying, and The Tunnel and the Light and On Grief and Grieving.

Parents: Ernst Kübler and Emma Villiger-Kübler

In 2007, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame for her work.

25 Posts in Top 50 Doctors (top50) Series

- 27 - Charles D. Kelman - Cataracts – 9 Mar 2023

- 28 - Cicely D. Williams, Kwashiorkor, Breastfeeding, Whistleblower – 21 Jun 2022

- 29 - Dame Cicely Saunders, Hospice – 23 Apr 2018

- 30 - David L. Sackett, Evidence-based Medicine – 2 Apr 2018

- 31 - E. Donnall Thomas & Joseph Murray, Bone Marrow Transplants – 23 Feb 2018

- 32 - Elizabeth Blackwell, women in medicine – 29 Jan 2018

- 33 - Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, stages of grief – 5 Jan 2018

- 34 - Watson & Crick, DNA – 2 Dec 2017

- 35 - Mahmut Gazi Yaşargil, Micro-Surgery – 24 Oct 2017

- 36 - George Papanicolaou, Cytopathology, Cancer – 29 Sep 2017

- 37 - Dr. James Parkinson, Parkinson's Disease – 1 Sep 2017

- 38 - Dr. John Snow, cholera – 20 Aug 2017

- 39 - Dr. Joseph Kirsner, GI Joe – 27 Jul 2017

- 40 - Lawrence (Larry) Einhorn, chemotherapy – 16 Jun 2017

- 41 - Robert Koch, modern bacteriology – 21 Mar 2017

- 42 - Stanley Dudrick, TPN – 28 Feb 2017

- 43 - Stanley Prusiner, neurodegenerative diseases – 25 Jan 2017

- 44 - Victor McKusick, medical genetics – 3 Jan 2017

- 45 - Virginia Apgar, anesthesiology & newborn care – 12 Nov 2016

- 46 - William Harvey, circulation – 12 Oct 2016

- 47 - Zora Janžekovič, burns – 26 Sep 2016

- 48 - Helen Taussig, blue babies – 3 Sep 2016

- 49 - Henry Gray, anatomy – 3 Jul 2016

- 50 - Nikolay Pirogov, field surgery – 11 Jun 2016

- Top 50 Doctors: Intro/Index – 10 Jun 2016

Advertisement by Google

(sorry, only few pages have ads)