ADHD Stimulants Lower Smoking Risk

I’m sorry, but I just have to say it: “neaner, neaner, neaner. See I told you so!”

I know that some of you thought you had me when five out of seventeen studies showed “no correlation” between being treated for ADHD and prevention of the increased incidence of smoking in this group of kids.

Consistent treatment with medication mitigates against smoking in ADHD children

Ok, I’ll get a grip and explain. For years we’ve all known that a whole lot of self-destructive, troublesome and simply annoying behaviors plague children (and their parents) who are diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD) and which are relieved when treated with medication.

Smoking Elevated in ADHD

Smoking is one of the serious ones. In fact children with ADHD are 200 to 300 percent more likely to smoke as their counterparts without the disorder; and, are more likely to start smoking at a younger age to boot. So, they are “over-represented” in all of the smoking statistics.

Also for years we’ve wondered if actually treating ADHD effectively made any difference in the children’s health and long-term life outcome. Over 17 studies have been done comparing treatment outcomes. Nine of them showed a benefit, but 5 showed no association, and 3 showed mixed results.

Now the doctors at Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, had the temerity to take the common sense approach of combining all the studies together and analyzing not just “were they treated” but “were they treated consistently and well” to see if that made a difference… and it did!

Voilà… everything became clear. “Children with ADHD who are consistently treated with stimulants show a clearly lower rate of smoking.” In fact, it negates the findings mentioned earlier and they no longer start earlier either – if they do start.

New Smoking Meta-study

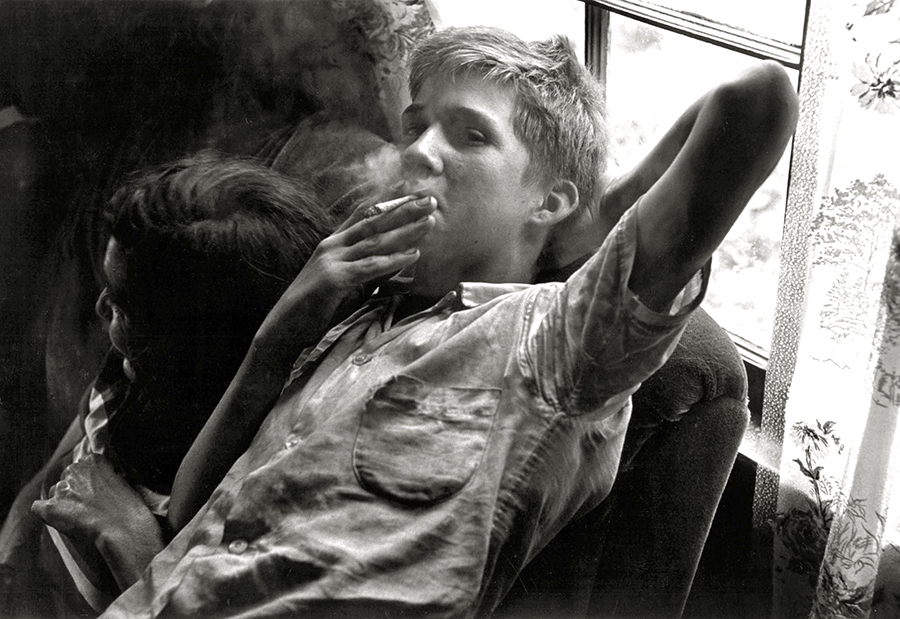

“Doesn’t smoking make me cool?”Fourteen of the seventeen studies I mentioned had gathered enough data on their subjects to be analyzed more deeply. So, there were 2,360 participants, including 1,424 treated and 936 untreated, who ranged from 4 to 18 years that were used in the study, making it the largest meta-analysis to date.

“Doesn’t smoking make me cool?”Fourteen of the seventeen studies I mentioned had gathered enough data on their subjects to be analyzed more deeply. So, there were 2,360 participants, including 1,424 treated and 936 untreated, who ranged from 4 to 18 years that were used in the study, making it the largest meta-analysis to date.

Children’s treatment and outcomes were followed from 2 to 26 years and the results were significant at the 95% confidence interval – pretty good.

Effects Of Treatment

When even breaking it down further, the smoking rate reversed in adolescents greater than young adults (P < .05) and in girls more than boys (P < .01). Interestingly, the "lessening" was also greater in children from clinics (i.e. referral centers) than those from community-based doctors (P < .01). Why? Who knows? BUT, it could have something to do with the accuracy with which the diagnosis of ADHD is made [Multidisciplinary clinics often use more "rigor" in making the diagnosis compared with private practice physicians]. OR, it may mean there is more effect in the children who have more significant symptoms and are therefore referred to specialists in the clinic. My money is on the former.

Consistent Treatment

When the Duke researchers analyzed why other studies had different results it seemed to be because they were looking at the wrong categories. Consistent and effective treatment isn’t the same as comparing those kids who were never treated to those who had any treatment at all even if it wasn’t correct.

“It is possible that reduced smoking among medicated youth occurs because ADHD symptoms and impairment are effectively mitigated by medication,” they said.

And, an interest and effort to do a good job in diagnosing the problem is crucial. It is NOT made in one or even two 15 minute visits to a family doctor sandwiched in between an office full of sick kids! Or, as a “by the way” afterthought during an appointment for something else – even a sports physical.

There are full check-lists of behaviors to carefully assess – not only by the parents in the home setting but by the teacher(s) in the school setting. Not to mention that the physician should also take a careful history of the problem and perform a full physical examination with attention to neurological findings – all of which often requires more than one extended (unrushed) visit.

And lastly, if the suspicion is there that medication might be helpful, you should know that a thorough and accurate diagnosis usually can’t be made without “before and after medication trial” rating observations by both parents and teachers – and it is best if at least the teacher is “blind” to which week the child was “on” and which week they were “off” the medicine. It really drives the diagnosis “home” when an independent observer identifies a change without knowing whether there were meds or not.

Higher risk of smoking in ADHD lowered by consistent medication treatmentFrankly, not all physicians are interested enough to take the time to be thorough in the diagnosis; so, unfortunately, not all children who receive treatment with medications actually have the correct diagnosis.

Higher risk of smoking in ADHD lowered by consistent medication treatmentFrankly, not all physicians are interested enough to take the time to be thorough in the diagnosis; so, unfortunately, not all children who receive treatment with medications actually have the correct diagnosis.

“It’s important to note that the children who benefited from stimulants in these studies were diagnosed with ADHD through careful and thorough diagnostic evaluations,” the researchers said. “We can’t conclude that medication will have these benefits for all children out there who are prescribed stimulants, and it is crucial to use formal diagnostic procedures to make sure that ADHD is truly what is causing the difficulties.”

What Is Consistent and Good Treatment?

Once the accurate diagnosis is made, what, then, is consistent treatment?

There is no compelling evidence against treating ADHD with medication or taking the medication consistently, even when not at school. It bears repeating: ADHD is NOT just a school problem. Some children do have a slightly decreased appetite when taking the medications; but, for many, if not most, the appetite returns with continued use.

There are a few children, however, whose weight plateaus and who need to try alternate formulations. Some patients benefit from dosage changes and some need some time off meds to “catch up,” like during the summer when school is out.

Especially when the parents have scored the child high on their observation sheets, I’ve always recommended that medication be given every day, even on weekends, because ADHD is NOT just a school problem! The child lives life at home too, and needs to function clearly and appropriately within the family and neighborhood – not to mention that most “little league” sports coaches and scoutmasters are grateful for a child who doesn’t add to the chaos.

Now, with this new evidence, I’ve begun questioning the rationale for when/if stopping medicines for a “break” during the summer is appropriate. Clearly, if weight loss is a concern there needs to be some form of a break. However, when exactly does a child make the impulsive decision to take up smoking or make other self-destructive decisions like taking drugs, initiating a pregnancy, “joyriding” or other such things? Only during school hours? Obviously not.

The thing that makes decisions based on this study a bit difficult is our standard and necessary approach of not taking any study as gospel until corroborated by observation, experience and repeatability. In spite of being a “meta” study comprised of a huge number of patients, it is, after all, one study and needs to be elucidated more fully. One must admit however that its findings do agree with observations and just do make sense.

I’m beginning to think now that, if we’ve shown that medicines are effective in a particular patient (therefore know the diagnosis is correct), they should be continued all the time unless careful observation and/or side-effects demand otherwise. Perhaps it’s like we’ve begun doing with child athletes – examining both before and after each sport season to do testing that can be compared with a post-injury repeat test, should there be an injury.

Physicians and parents could feel more comfortable to continued meds with a tad more frequent “touch-bases” visit, especially if there were emphasis on the potential side-effect’s observations, measurements and tracking.

Truly, developing habits and making choices which cause success in school is a HUGE benefit to a child’s life; however, NOT making an impulsive choice to smoke just may be one of the most important things that come out of treatment for the disorder – even if it was the only one.

[Pediatrics. Published online May 12, 2014]